Chapter 16: Of Maeglin

One of the really wonderful things about having to reread a chapter of the Sil with the express purpose of considering one’s own perspectives on the narrative so that they can (hopefully) be articulated, is that it so often reveals details and nuances never before appreciated. This is certainly true of this chapter for me. I always knew that it was a dark tale, sad and unsettling (kind of creepy, really). But I had never really considered the depth of tragedy and the terrible scope of consequence that marks what surely must be one of the most dysfunctional families found in any of Tolkien’s writings.

From the very first passages introducing Aredhel Ar-Feiniel, there is a sense of fierce pride and a kind of concealed, simmering desperation to her character. In some ways, she reminds me of Éowyn: a noblewoman endowed with great strength and intelligence, who yearns for independence from the confines of her courtly station. They even share the same title - "The White Lady" of their respective kingdoms. In other ways, the comparison doesn’t quite hold up, as it becomes apparent that Turgon’s word as lord of Gondolin, and the decree of isolation that all his subjects, male and female, must obey, can be openly and successfully challenged by his tenacious and willful sister. Her decision not to ride to Hithlum to stay with Fingon, her brother, but instead to ride south to the realm of her cousins and friends, Curufin and Celegorm, is like the impetuous decision of a rebellious teenager, asserting her independence regardless of the advice of those “wiser in the ways of the world”.

Once again, the far-reaching consequences of Fëanor’s unforgiveable actions at Alqualondë force a direction in the story. Rather than coming safely to Himlad through Doriath, Aredhel and her companions are forced to brave the treacherous shadows of Ungoliant’s making in Nan Dungortheb, so that her three escorts are forced to return to Gondolin without her, while she, through her own courage and resourcefulness, finds the way to Himlad. There, she awaits the return of her cousins, who have gone

“riding with Caranthir” (I love the allusion to the Elvish perception of time that has them gone on this little foray for the better part of a year!) Once again, Aredhel becomes restless, and begins

“seeking for new paths and untrodden glades”, until she finds herself in the great wood of Nan Elmoth.

It is at this point of the story that some of those new thoughts (or at least, more consciously considered thoughts) entered into my reading. Firstly, I had never really “clued in” to how similar the Dark Elf, Eöl, was to Aredhel in his “backstory”. He too, felt

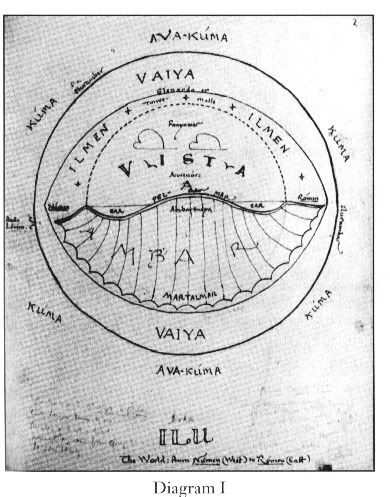

”restless and ill at ease” when abiding within the boundaries of Doriath, no matter how beautiful and blessed that land may have been; and he too fled from the confinement of a protected and hidden realm. I think that in a subtle way, Tolkien was pointing to the duality of these guarded Elvish kingdoms: that in keeping the evils and perils of the surrounding world

out, they also serve to force their inhabitants to remain

in. It is a “fortress existence”, a siege mentality that cannot help but feed a shadow that quietly gnaws at the bliss and beauty of the culture within. I believe Lothlórien is also touched by this dilemma, but I think that may well be the topic of another discussion.

Something else that never really “hit” me before is that the meeting of Aredhel and Eöl takes place in the Nan Elmoth, where Melian and Thingol first met, and, in a rather perverse way, parallels that meeting. Aredhel is drawn deeper and deeper into the great wood by the “enchantments” of Eöl, much like Thingol was drawn to Melian, but there is no “magic” timeless love that is kindled at their first touch; there seems to be no love at all, really. For Eöl, it is “desire” that is roused, and for Aredhel…….well, this is where things get a little unsettling. Tolkien writes that she was not

“wholly unwilling” in her union with the Dark Elf, but within the greater tale that contains so many great and noble love stories, this seems somehow "not as it should be" between two of the Eldar. Aredhel, although given somewhat more independence to

“fare alone as she would”, basically trades in the “bonds” that she felt in Gondolin for the new, and far more sinister bonds of a loveless marriage and a life doomed to darkness and twilight.

The result of this dysfunctional union between “The White Lady” and “The Dark Elf” is, of course, Maeglin, the main subject of this chapter, and one of the most pivotal characters in the histories of the Noldor. It strikes me as so sad that his “mother-name” of “Lómien (Child of the Twilight) can only be spoken in Aredhel’s heart, as it is in the “forbidden tongue” of the Noldor. It’s also interesting to consider that this, as the mother’s choice, would be a “name of insight”, for although it seems to merely represent the circumstances of his birth and rearing in the physical world, it can also be seen as describing his fate: first caught between the widely differing “worldviews” of his parents, and later (as will be seen) caught between his own unrequited love and heart’s desire, and the laws and customs of his people. I love the passage that recounts Eól’s naming of his son (which occurs a full twelve years after his birth):

Then he called him Maeglin, which is Sharp Glance, for he perceived that the eyes of his son were more piercing than his own, and his thought could read the secrets of hearts beyond the mist of words.

*pauses to sw00n for Tolkien’s masterful use of language*

Maeglin seems to naturally inherit a restless and questing spirit from both his parents. It is said that he has an eagerness to learn the craft lore of the Dwarves (as did his father before him). This trait to be driven by the “making of things” (especially without successfully balancing the "art" of creation with the "science" of production) always seems to be marked as something of a double-edged sword by Tolkien, considering the ultimate fates of Saruman, and the Elves of Eregion, and perhaps even Fëanor himself. But upon this reading, I also notice that Tolkien writes:

His words were few save in matters that touched him near, and then his voice had a power to move those that heard him and to overthrow those that withstood him.

Whoa……now doesn’t that sound an awful lot like Fëanor?

Though he resembles his father in

“mood and mind” and inherits from him the gift of metalcraft, Maeglin

“loved his mother the better”, and is transfixed by her tales of the glory and valour of their shared kin in both Eldamar and Middle-earth. Up until now I always considered the following passage as indicative of Maeglin’s darker designs:

All these things he laid to heart, but most of all that which he heard of Turgon, and that he had no heir; for Elenwë his wife perished in the crossing of the Helcaraxë, and his daughter Idril Celebrindal was his only child.

Now, I’m not so sure that this is actually a conscious thought on Maeglin’s part to find a way to insinuate himself into a position of power. Perhaps it’s more a yearning to belong; to escape from his life of isolation and find a connection and a place with “his people”. Either interpretation is plausible, I believe.

There seems to me something inherently unpleasant in the way Tolkien describes how Maeglin

“bides his time”, hoping

“to wheedle the secret” of Gondolin’s location from his mother, or

“perhaps to read her unguarded mind”, but maybe it is the sheer desperation to get away from the suffocating environment he is forced to endure that puts these dark desires in his heart. I’m finding Maeglin to be a far more sympathetic character with this reading, and I’m having some interesting “second thoughts” about his motives.

Whatever his motivations, Maeglin finally convinces his mother to flee from Nan Elmoth and Eöl’s restrictive authoritarianism, with the stirring words:

”What hope is there in this wood for you or for me? Here we are in bondage, and no profit shall I find here; for I have learned all that my father has to teach, or that the Naugrim will reveal to me. Shall we not seek for Gondolin? You shall be my guide, and I will be your guard!”

Once again, Fëanor comes to mind, and his powerful words to the Noldor before their departure from Aman.

In a “parting shot” at Eöl, Aredhel tells her servants that she and her son have gone to seek the sons of Fëanor, something that he has expressly forbidden her from doing because of his deep dislike and distrust of the Noldor. Riding in fury after them, Eöl encounters Curufin, and I think the resulting exchange between these two darkly menacing characters is an absolutely wonderful rendering of simmering hatred, barely contained within the formalities of carefully chosen words.

Then Eöl mounted his horse, saying: It is good, Lord Curufin, to find a kinsman thus kindly at need. I will remember it when I return.” (ouch!)

Then Curufin looked darkly upon Eöl. ”Do not flaunt the title of your wife before me,” he said. “For those who steal the daughters of the Noldor and wed them without gift or leave do not gain kinship with their kin. I have given you leave to go. Take it, and be gone.” (double ouch!)

Eöl continues his pursuit of Aredhel and Maeglin and sees them take the hidden path to the first Gate of Gondolin. Inside, both mother and son are joyously received by Turgon, who, unlike Curufin, warmly extends the hand of kinship to his sister-son. But poor Maeglin, above all the splendours of Gondolin, espies Idril, and falls immediately and hopelessly in love with her.

Poor Maeglin: I never thought I would write those words. But after his life of darkness, is it any wonder that this “golden” child of the Vanyar and Noldor would seem to him

“as the sun from which all the King’s hall drew its light”?

When Eöl is brought before Turgon, once again the hand of friendship and kinship is offered, but the Dark Elf utterly rejects the authority of Lord of Gondolin. He is willing to surrender his claim upon Aredhel, but not upon Maeglin, and commands his son to leave

“the house of his enemies and the slayers of his kin”.

But Maeglin answered nothing.

Four simple words, but my goodness, they do speak volumes, don’t they?

Turgon then answers Eöl’s defiance with words that actually remind me a little of Boromir’s at the Council of Elrond:

By the swords of the Noldor alone are your sunless woods defended. Your freedom to wander there wild you owe to my kin; and but for them long since you would have laboured in thraldom in the pits of Angband.

Turgon finishes his speech with no uncertainty at all regarding the fate that Eöl must now accept for both himself and his son: to dwell in Gondolin for the rest of their lives, so that the secret realm may not be endangered by their knowledge of its location. But Eöl has come prepared for the worst, and knowing that his life is now forfeit (for he would never accept such terms), he attempts to take his son’s life as well, refusing to lose his absolute claim on Maeglin as solely “his own”, like a piece of property, really. Aredhel throws herself in the path of the poisoned dart that has been aimed at her son and is mortally wounded, and Eöl is subdued in his rage and is bound and led away:

But Maeglin looking upon his father was silent

Because of his murderous act, Eöl is sentenced to death, cast down from the sheer walls of the city to be broken upon the rocks below. His final words are a curse upon his son……a curse working within a curse, it would seem.

”So you forsake your father and his kin, ill-gotten son! Here shall you fail of all your hopes, and here may you yet die the same death as I.”

......

And Maeglin stood by and said nothing.

The chapter ends with a recounting of Maeglin’s rise to greatness among the Gondolindrim. Of how his knowledge of smithcraft and mining helped achieve weapons of strength and keenness that would be needed in the dire days that lay ahead in the war against Morgoth. Of how wise in counsel he became, a careful and wary strategist whose skills in thought were matched by his valour and fearlessness in battle. There is an intriguing line that I never noticed before in the final passage of the chapter that foretells that one only will surpass his greatness in Gondolin:

Thus all seemed well with the fortunes of Maeglin, who had risen to be mighty among the princes of the Noldor, and greatest save one in the most renowned of their realms.

This is followed by the desperately sad truth that he carries secretly in his heart: his love

“without hope” for his own cousin, Idril, and the resulting grief that

“robbed him of all joy” in spite of all the glory and power he achieves. And Idril, like Maeglin himself, able to read the hearts of others “beyond the mist of words”, perceives this love, and is repulsed by it for

"it seemed to her a thing strange and crooked in him.”

Poor Maeglin: forever alone and without love, carrying the legacy of his parents own “strange and crooked” union, as well as being swept along by the far-reaching waves of bitter consequence that Fëanor set in motion. He carries the doom of Gondolin within him like some kind of dormant virus, waiting to be awakened. What terrible burdens to bear.